PODGORICA, 01.10.2019. – Journalist Marina G. (real name known to the author of the text) has decided to write about fees that one public company charges citizens. As a penalty for non-payment, the company envisaged termination of services. After consulting with the lawyers, she has realized that there was a legal possibility for these fees to be abolished or declared illegal. She did everything journalists do when writing analytical articles – she interviewed lawyers, citizens, representatives of the non-governmental sector and then – representative of the mentioned public company. She met with the director, explained to him what the citizens’ complaints were and how the lawyers interpreted the fees. The gentleman in the leather armchair had several papers in front of him and he tried to explain and justify collection of the fees and sanctions provided for non-payment.

The journalist obtained the consent of her editor to publish the article. It wasn’t long after the article was published, and Marina’s phone rang. It was the owner of the media she worked for, who invited her to interview. Shortly afterwards, Marina had to publish a response stating that the text was tendentious and written with the aim of jeopardizing the business of the large company.

But the journalist didn’t stop and has continued to investigate. Among other things, she has researched a property card of the public company director. She was informed that he didn’t provide true public information about his own property and that he had “hidden” more real estate in the property file. This time, Marina didn’t get the editor’s consent to publish the text. She decided to give all the information to a colleague from another media. The text was published in another media and the director of the company announced a lawsuit for reputation infringement against their editorial staff.

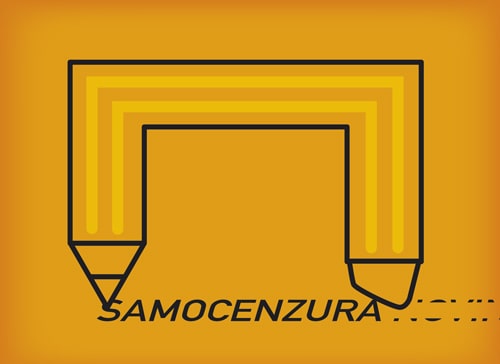

What has happened in this story? Well, self-censorship, among other things. Marina’s editor didn’t have courage to allow publication of the second text. The journalist also, in a certain sense, agreed to self-censorship, not opposing the editor and giving her effort to the colleague.

Self-censorship is bigger problem than censorship. Censorship is sometimes discovered, but how many important information we never know because someone was “holding back” himself? “Media censorship is forbidden,” states the Montenegrin Law on Media. But what about self-censorship? Can you ban editors and journalists from being scared? Can laws affect their conscience?

Article 28 of Draft Law on Media states joint responsibility – founder, editor-in-chief, column editor or journalist are jointly responsible for the damage they cause to someone. Yes, there should be sanctions for damages done. But the question, that has already been raised in the public, is – will this provision increase the amount of self-censorship.

Some editors and journalists fear lawsuits, while the braver ones suffer monetary losses. Undoubtedly – both the law and ethical norms should be respected. But Montenegro has problems in both fields.

According to the already mentioned Draft Law on Media, journalist has the right to refuse to prepare or write a text that is contrary to the Law and the Code of Ethics, with a written explanation to the editor-in-chief. For this reason, an employer can’t terminate journalist’s employment, can’t reduce journalist’s salary and can’t place him at a disadvantage. However, what we do not know is – how will these conditions be fully guaranteed? Pressures on journalists can be very subtle, covert and difficult to prove.

If journalist/media is charged and must pay to someone for the harm done, there must be proven guilty. Another question we are obliged to answer is – how credible are those who decide on the existence of this guilt? Various affairs diminish confidence in the Montenegrin justice system.

All of this, of course, doesn’t mean that journalists and the media should have unlimited freedom and publish unverified or untrue information. As stated in the Code of Ethics, respect for ethical norms is not only a duty but also a journalist’s interest. The facts are inviolable and the incomplete and incorrect information must be supplemented or corrected.

However, this shouldn’t be forgotten: Journalists must be critical observers of “those in leather armchairs.” Unfortunately, many who didn’t accept to be “microphone holders” are no longer engaged in journalism. One of them is Marina G.

Dragana Zaric, journalist

The text was created within the project “Monitoring for free media” implemented by the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro within the framework of a major project “Judicial Reform: Upgrading CSO’s capacities to contribute to the integrity of judiciary” financed by the European Union, and implemented by the Center for Monitoring and Research (CeMi) in partnership with the NGO Center for Democracy and Human Rights (CEDEM) and the Network for the Affirmation of European Integration Processes (MAEIP).