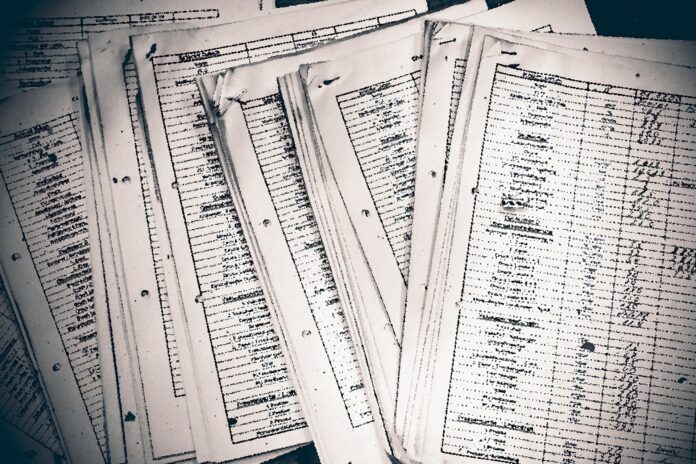

During the past year, the newspapers Informer, Alo, Vecernje novosti, Kurir and Srpski telegraf published at least 1,174 manipulative headlines on their front pages, most often in the form of unfounded or biased claims, disinformation or manipulation of facts, according to the latest analysis of Raskrikavanje. This number also suggests that there was an increase in the number of disputed claims on the front pages compared to the year before. At the same time, the companies behind these tabloids received more than 800 thousand euros from public budgets in 2022.

Last year, Informer had the most manipulative news – disinformation, biased or claims for which there was no evidence – as many as 363. It is followed by Srpski telegraf with at least 253, Vecernje novosti with 238, Alo with 198, and Kurir with 122.

The results of the analysis show that last year more manipulations were published on the front pages than the year before. In 2021, Raskrikavanje detected less than 1,000 disputed or incorrect claims on the front pages, including six tabloids (as well as Objektiv, which stopped being published last year).

The reason for this could be the important events that marked the last year. For the tabloids, these events were a “treasure house” of various manipulations – above all, the war in Ukraine and its consequences, the parliamentary and presidential elections in April and the events in Kosovo.

Depending on the period and events, various actors took turns on the front pages, but a few of them stood out in particular. In the first half of the year, we had the opportunity to see opposition leader Dragan Djilas, as well as Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky, while in the second half of the year, the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Albin Kurti, often appeared (in a negative context). The only one who continuously appeared throughout the year, almost always in a positive, and sometimes in a neutral context, was Aleksandar Vucic, whose face appeared on the front pages of these five newspapers at least 851 times.

The dominant form of manipulation, as we have noticed, were unfounded headlines for which there was not enough or even no support with evidence and arguments in the text itself. In addition, biased claims in the form of comments, insults or “cheering” at the expense of various actors dominated, which made the tabloids openly take sides. We have recorded several examples of manipulation of facts, as well as disinformation and fake news.

You can read our assessment methodology here.

We did not analyze news from show business and sports, except for the events surrounding the deportation of Novak Djokovic from Australia in early 2022.

Informer war games

The pro-regime tabloid Informer, as detected by Raskrikavanje’s journalists, was the undoubted champion of manipulations on the front pages last year as well – there were at least 363 of them, so more than once a day since 306 issues were published during the year.

The year began with a reckoning with the leaders of the opposition, given that Serbia was expected to hold elections in the spring. We could read articles about “Savo CIA Manojlovic” preparing “bloody riots”, Ponos as a “NATO candidate”, “fake environmentalists”, “haters” and “wretched people” from the opposition. Running a campaign against them, this tabloid often claimed they said something they didn’t – “twisting” other people’s statements was one of the most common forms of manipulation last year in Informer.

At the end of February, Informer opened the era of war manipulations with the now well-known front page which claimed that “Ukraine attacked Russia”, and during the following months, this tabloid wrote about how Putin “trampled” Ukraine, how his “lightning strike” happened and how Ukraine is “begging for mercy” on its knees. The image of the President of Russia appeared 86 times on the front pages.

As the war progressed, the tabloids wrote about the food and energy crisis, but in European countries: “The EU is begging for gas” or “Switzerland – whoever heats the apartment to more than 19 degrees goes to prison”, which we found to be complete disinformation.

This headline also caught our eye: “The world is threatened by a great famine”, immediately followed by the claim that “Serbia has enough food”. By the way, this was the usual narrative of the pro-regime media when it comes to the economic consequences of the war – they are almost starving in the world and everything is under control in Serbia – which Raskrikavanje also wrote about last year in a major analysis of media coverage of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

In the first half of the year the main villain, like a year before, was Dragan Djilas, whose picture was published at least 32 times in a negative context. In the second half of the year – with the worsening of the crisis in Kosovo – the “batton” was taken over by the Prime Minister of Kosovo, Albin Kurti. His face appeared on the covers of Informer at least 49 times – they called him, among other things, a “ticking time bomb”, “Shiptar scum” and “psychopath from Pristina”.

Reporting on Kosovo was accompanied by frequent announcements of war, especially at the time when the Kosovo government tried to introduce RKS plates. Back then, Raskrikavanje also analyzed what the media propaganda stoking the fire from Belgrade and Pristina looked like.

The word “war” was one of the most frequent on the front pages of this tabloid.

At the same time, the personality cult of President Aleksandar Vucic was carefully maintained, appearing on the front pages 142 times, almost exclusively in a positive context – he prevented announced wars and calmed tensions, “defended Serbia” and “smashed” opponents.

Srpski telegraf “dominated” with Vucic’s photos

Srpski telegraf published at least 253 unfounded, biased and other manipulative claims on its front pages.

The main good guy in this tabloid was, as expected, Aleksandar Vucic, whose photo appeared at least 242 times on the front pages alone – by far the most of any other newspaper. We looked at his face when they quoted him, when they reported on a state visit, when the topic was investments, but also when someone (unsuccessfully) tried to “break” him.

Srpski telegraf showed its support for the president by describing his policy as “wise”, him as a man who leads a “lion’s fight”, “does not know defeat” and “rejects every pressure like a wall”. At the end of the election campaign, he was called “Alexander the Great”, and a day later, an illustration of Vucic as the Terminator was published on the front page, featuring the symbols of Belgrade and cranes on construction sites in the background, with the inscription “MACHINE”.

The narrative that pro-regime tabloids “weave” around Vucic should convince readers not only of his strength but also of his vulnerability. That’s how Srpski telegraf presented him during the last year – as a victim, a man who is “broken by both the East and the West”, who “endures unprecedented pressures” and who is an “on-duty culprit”.

The second record holder for the number of appearances is Vladimir Putin – his photo was published at least 162 times in this tabloid, significantly more often than in other newspapers. Srpski telegraf, unlike the others, changed its approach to reporting on Russia and Putin during the war, which you can read about in a separate analysis.

In addition to having a good guy, every story needs a bad one as well. Last year, it was Albin Kurti whose face appeared on the front pages at least 32 times in Srpski telegraf. They claimed that he was “primitive” and “evil”, and he was repeatedly accused of “wanting war” and “wanting blood”.

When they reported on the meeting between the two statesmen at the negotiation table in Brussels, Vucic was presented as the dominant one. For example, at the end of November, they published a text about how “Kurti can’t look Vucic in the eyes” – based on the “analysis” of his body language, they determined that he “demonstrated extreme fear and discomfort in direct conversations with Aleksandar Vucic, unlike Vucic which seems extremely firm and prepared”. As proof, they attached several photos of Kurti looking at the papers on the table or at Jozep Borelj and Miroslav Lajcak, who were also at the meeting. However, there is also a photo from the same meeting on the website of the European Council, where Kurti looks Vucic in the eyes.

Srpski telegraf also settled accounts with the recent associates of Aleksandar Vucic. Thus, they claimed that the former Minister of Energy, Zorana Mihajlovic, was “collaborating with the opposition”, that she was “blackmailing and attacking because she is losing her position” and that she was “hitting directly at Vucic”. Without evidence, they accused her on several occasions of giving information to the newspaper Nova because she was afraid of losing her position, and of “paying Solak’s media to advertise that she is hard-working, smart and has a tidy house”.

The former defence minister, Nebojsa Stefanovic, did not fare better either. After the interview that former state secretary Dijana Hrkalovic gave to Objektiv, accusing Stefanovic of protecting Veljko Belivuk, Srpski telegraf called for his arrest: “There is no going back now, country, arrest”. Almost every mention of Stefanovic was followed by biased or sensationalist headlines such as “Fear, Nebojsa”, “The minister hid in a mouse hole”, “Stefanovic collected debts for Saric”…

Vecernje novosti and Serbs as eternal victims of regional and western plotters

Third on the list in terms of the number of manipulations detected (at least 238 of them) is Vecernje novosti.

This paper very often manipulated by presenting doubts and speculations as facts, unjustified generalizations, statements like “it is without a doubt” for things that are suspicious and unreliable, by subtly inserting journalistic, suggestive comments into factual reports such as “the blackmailing tone of Washington” or “hot heads in Kyiv”, and it also happened that they did not have a single source in the text, that is, they made decided claims without any substantiation.

Vecernje novosti did not particularly deal with Vucic’s opposition or people from the SNS, but compared to all other newspapers, they traditionally dealt mostly with the “enemies” from the region – highlighting Albin Kurti, Albanians and Croats in a negative context.

Kurti appeared on the front pages of Vecernje novosti mostly in a negative context and with the use of inflammatory rhetoric, often without evidence for the written claims. In the black-and-white perspective of Vecernje novosti, the matter looked like this throughout the year: Kurti was preparing various atrocities in cooperation with allies in the West, and he received support from them against the Serbs, who were often uncritically portrayed as passive and victims. As this newspaper claimed all year, many people were working against the Serbs – Kurti, the Albanians, Milo Djukanovic, the European Union, the Croats, NATO…

The good guys were Russian President Vladimir Putin, but also Milorad Dodik, who was portrayed as one of the few cross-border friends of Serbia. However, even in Vecernje novosti, the most represented actor was Aleksandar Vucic, whose photo appeared on the front page as many as 161 times, i.e. almost every other day.

Vecernje novosti maintained his cult of personality similar to Informer – by building tension for several days with harsh and unfounded words and announcements of war, only for him to dispel that tension in one day. So, for example, ten days before the end of the year, practically every day, there were dramatic front pages about the crisis with the barricades in Kosovo – “Kurti wants a massacre at the barricades”, “Kurti’s terror with the approval of Germany”, “Vucic’s brother and son on the list to be killed”, “Kurti’s police officers fired shots at the Serbs”, “He raised the army to attack the Serbs”, “They want to kick us out of Kosovo once and for all”, and after that dramatic week came the resolution in the form of the president: “Guarantees received, they remove the barricades” while featuring a large photo of Vucic.

The foreign policy topic that dominated the number of manipulations in this pro-regime paper was the war in Russia. As we wrote in last year’s analysis, Vecernje novosti reported on the war like the PR centre of the Kremlin – by dominantly relying on Russian sources and reporting in favour of Russia and from a Russian perspective. All possible civil crimes in Ukraine were denied and relativized, with claims that it was a staged event “like Markale and Racko”.

Last year, Vecernje novosti did not miss the opportunity to deny the genocide in Srebrenica with headlines such as “Srebrenica, Racak, Bucha, one face of propaganda”, “Serbs attacked to take revenge, NATO handed over Srebrenica”, or “Signature on genocide first, then entering Potocari”, where they claimed that everyone who wants to visit the memorial centre in Potocari will have to sign at the entrance to acknowledge the genocide. As they reported from this centre, that was not true.

Alo: Manipulation of statements and Djilas where he is not there

Last year, we recorded at least 198 biased, unfounded or otherwise manipulative news on the front pages of the tabloid Alo.

One of the characteristics of this tabloid is that the claims of various analysts or politicians are often presented on the front pages as unquestionable truth. What looks like a fact on the cover, in the text turns out to be someone’s assertion (which does not have to be true), mostly unargued, speculation or opinion.

Even this tabloid did not deviate from the usual template of reporting according to which other pro-regime media also report – there are good guys (Vucic) and bad guys (Albin Kurti, opposition leaders, Croats).

Aleksandar Vucic appeared on the front pages of this newspaper at least 122 times last year, that is, on average every third day, mostly in the role of a dominant leader.

Thus, before the elections itself, Alo assessed the individuals who supported Vucic as a “dream team”, and his policy as “responsible and statesmanlike”. Vucic’s speech before the UN General Assembly was described by Alo as “historic”, and in their ecstasy, they stated that with this speech, he “dismantled world hypocrisy” and “told everything to their face”. To illustrate the text, as Raskrikavanje wrote at the time, they used a photo of a full hall, which was actually taken during the address of the Ukrainian ambassador to the UN, while the hall was half empty during Vucic’s speech.

Even Alo did not spare Albin Kurti, the number 1 villain in the previous year, of harsh words. They described him as a “thug”, “lunatic”, “criminal”, “terrorist”, “Serb hater” and “clown from Pristina”. The negative campaign against Kurti was most pronounced in the summer when Kosovo announced new measures regarding personal documents, as well as at the end of the year when Kosovo’s Serbs set up barricades due to the arrest of a Serbian police officer.

One of the headlines from that period shows what manipulative reporting looks like when the claim that “Kurti openly announced that he would kill Serbs” and the comment “Creepy” appeared. Inside the newspaper, the reader learns that the reason for the text is Kurti’s statement to the Guardian in which he actually said that “We are concerned that the removal of the barricades will not exclude the victims”. The text shows that not only did he not announce the killing of Serbs, but on the contrary – he stated that “We want to be as careful as possible to ensure that there will be no destabilization and that there will be relative peace and security”. However, this sentence was not found in the text, but Prime Minister Ana Brnabic, Defense Minister Milos Vucevic and Director of the Office for Kosovo and Metohija Petar Petkovic commented on the fabricated threats in the Guardian.

They directed derogatory words at other “enemies”, such as Dragan Djilas, who they called “opposition tycoon” and “hypocrite”, and put him on the front page even when they didn’t even mention him in the text. Thus, we noted the headline in which Alo claimed that “for Djilas and Marinika, Serbs are murderers”, referring to an article in Danas. In that text, however, there is neither Djilas nor Marinika Tepic, but it conveys the testimony of a witness before the court in The Hague who claimed that Serbian forces killed civilians during the war in Kosovo. Alo “justified” the front page with the following words: “In the newspaper Danas, which is under the control of (…) Djilas and his right-hand Marinika Tepic, the presentation of Serbs as murderers, rapists and criminals continued”.

By the way, the publisher of Kurir is Adria Media Group, which has been hiring a manager for ethical standards since 2020. As they boasted at the time, they were the first media company in Serbia to hire an expert in journalistic ethics – Petar Jeremic, a former member of the Appeals Commission of the Press Council, is in that position – with the aim of “improving respect for ethical standards”.

Improved ethical standards of Kurir: “Whoever sleeps with Djilas, wakes up being peed on”

Last year, at least 122 unfounded or biased claims, as well as other types of manipulation, were published on the front pages of Kurir.

Vucic’s picture appeared on the front page on average every other day – at least 184 times – which puts this tabloid in second place, behind Srpski telegraf. The president was presented either in a positive or neutral context, and the positive attitude towards him was often expressed in just one word: “Stable”, “Determined”, “Principled”, “Consistent”, “Responsible”, “Strength”…

Similarly, Kurir also showed bias towards some other actors, for example, Albin Kurti, whose political moves were followed on the front pages by the epithets “Gauzy” of “Perfidious”, while the moves of the opposition leader were evaluated with “Irresponsible” and “Impotence”. Politicians and other actors from Croatia and Montenegro were also described with the following words: “Pathetic”, “Desperate move”, “Shame”, and “Egocentric”…

For example, they stated that Dragan Solak was “a money guarantor” and that he was “washing his biography”, and that headline was followed by the comment “A frog saw a horse being calked”. We recorded several other cases of the use of folk sayings in a similar context (“The village is burning and Zorana is combing her hair”), and “Who sleeps with Djilas wakes up being peed on” was especially interesting. This title announced “analysis of the political liquidations of Dragan Djilas”.

And Kurir, like other tabloids, sometimes used filters on photos of certain actors if they were “the bad guys”. Thus, Vucic’s face in the photos is “without wrinkles” and without the contrast that was used for photos of Kurti or opposition politicians whose faces on some covers looked tired, sick and ominous.

In addition to biased ones, there were also unfounded headlines, that is, claims for which there was no evidence or adequate arguments in the text itself that would “justify” it.

For example, they reported the alleged statement of the mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko, that “Serbia occupied Kosovo”, which Raskrikavanje considered unfounded, and Klitschko himself quickly denied this. They also wrote that North Korea is sending Putin 100,000 soldiers, which fact-checkers in the world assessed days before as a claim for which there is no evidence – moreover, such a thing was denied to Newsweek by the Russian Ministry of Diplomacy.

Manipulations guarantee readership, readership guarantees earnings

The companies behind these papers have, at the same time, concluded business contracts with the state, local self-governments and institutions during the past year.

They made money primarily through tenders for advertising, and to a lesser extent through tenders for project co-financing. More than 800,000 euros were paid to them from public budgets through these contracts, which you can read about in a separate text of Raskrikavanje.